Witness is a reader-supported publication operating under the anti-literary, anti-everybody-but-the-filthy-rich apocalypse of the Trump/Vance/Musk regime. If you are able, please consider purchasing a subscription for you or someone you love. Thank you.

“Are you sure, sweetheart, that you want to be well? I like to caution folks, that’s all. No sense us wasting each other’s time, sweetheart. A lot of weight when you’re well. Now, you just hold that thought. You just hold that thought. In the last quarter, sweetheart, anything can happen. Folks come in here moaning and carrying on and say they want to be well. Don’t know what in heaven and hell they want. Just this morning, fore they rolled you in with your veins open and your face bloated, this great big overgrown woman came in here tearing at her clothes, clawing at her hair, wailing to beat the band, asking for some pills. Wanted a pill cause she was in pain, felt bad, wanted to feel good. You ready? So I say, ‘Sweetheart, what’s the matter?’ and she says, ‘My mama died and I feel so bad, I can’t go on’ and dah dah dah. Her mama died, she’s supposed to feel bad. Expect to feel good when ya mama’s gone! Climbed right into my lap. Two hundred pounds of grief and heft if she was one-fifty. Bless her heart, just a babe of the times. Wants to be smiling and feeling good all the time. Smooth sailing as they lower the mama into the ground. Then there’s you. What’s your story? As I said, folks come in here moaning and carrying on and say they want to be healed. But like the wisdom warns, ‘Doan letcha mouf gitcha in what ya backbone caint stand.’ Just so’s you’re sure, sweetheart, and ready to be healed, cause wholeness is no trifling matter. A lot of weight when you’re well.”

—Toni Cade Bambara, The Salt Eaters (1980)

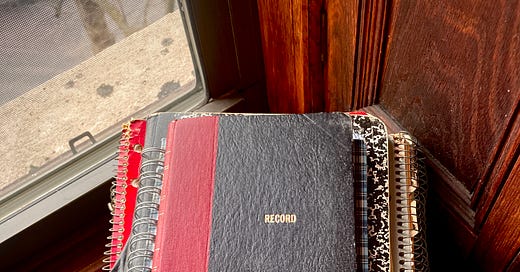

Sometimes I forget how long I’ve been writing until I come across the evidence.

You see the photo above? That’s a recently rediscovered trove of poems that I started writing just as I turned 12 years old. I literally had to dust off the covers. I had to carefully handle aging, yellowed paper because some of it was more delicate than I would have imagined (is 42 years that long ago? Damn!). I forgot that old paper can have a smell. That generations of certain kinds of insects can make a home inside your ideas and leave their carcasses behind because they’re not among the species that bury their dead or set them aflame.

I actually thought I lost these poems—to time, to moves, to thieves, to irresponsibility, to my mother’s extraordinarily low tolerance for clutter (which I’ve inherited)—so I was surprised when I opened a random box that I thought had something else in it and—BOOM—there they were. Reflecting upon it, I think I might have been hiding them from myself because I was ashamed of them. A lot of what I wrote then was overly sentimental, self-pitying, desperate, trite, and rhyming for no other reason than I thought that poems were “supposed to rhyme.” It was all childish, I guess you can say. But that makes perfect sense because I was, in fact, a child when I wrote them.

It took backbone I was sure I didn’t have to flip through those old notebooks. If you didn’t know, time traveling in America carries with it a great deal of danger for Black people. Any time we visit is liable to incarcerate or incinerate us. But I did it anyway. In doing so, in taking the closer look I didn’t want to take, I found that some of the poetry…some of it was too grown, too honest, too knowing, too much for a 12-year-old to have written; and appropriately written in mostly blue ink because in reading them, what I felt most overwhelmingly was the blues. All of the poems—every single one of the over 1,000 poems—were about a pain, longing, and loneliness that feels very right now. Many of them were about an unarmed boy waging a war against mighty gods and their earthbound armies, and losing. I turned 54 yesterday, but it was clear to me how much that little boy ain’t go nowhere. I concluded that past, present, future…those words were meant to mean different things but don’t have nary a meaningful difference.

I’m reluctantly remembering how, at the time that I wrote them, I thought the poems were good. I couldn’t share them, though, because they revealed things that could have gotten me killed (my queerness, for example). I’m glad that they were too private and risky to share because most of of them were actually terrible; and given the fragile condition I was in as a closeted baby boy, I’m not sure I would have been able to withstand embarrassment on top of shame before the eventual swing of the killing blow. That wasn’t just some paranoia of youth. Like I said: 12-year-old me knew too much.

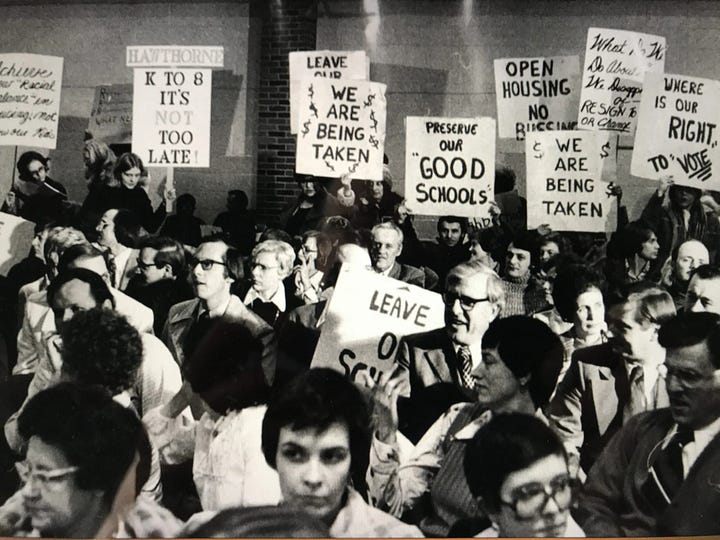

As I encountered what 12-year-old me saw and endured, I thought about this interview where Toni Morrison, perhaps the greatest writer of all time, was making a moral argument to her interviewer, a white woman. You know the interview, it’s the one that went viral because Morrison said to the interviewer: “You don’t understand how racist that question is, do you?” In any event, the moral argument Morrison made was about how white mothers had banded together to stop Black children from integrating into all-white schools and the depths to which they sunk in order to enact their plans. Morrison insisted that Black mothers would never do what the white mothers did, like turn over school buses, with Black children in them, to keep the children from entering segregated schools.

I took great comfort in believing Morrison, that Black mothers could never stoop to the level of depravity that white mothers had. But something about that felt too easy, too confident, too certain. And I’ve come to learn that where there’s certainty, there isn’t always knowledge. The nature of our species is such that no person is above tripping and falling into their absolute worst selves. That’s the lesson of history, the legacy of civilization. Could Morrison’s assertion have limits?

I had to look no further than my own childhood for the answer. I swear on everything that no one’s race, sex, or gender—indeed, no one’s parental status—had ever done anything to alter or halt the myriad measures of violence they directed toward a queer child like me. At all. I could detail each and every one of the abuses they heaped upon my fledgling body—from emotional to psychic, from physical to verbal, from sexual to spiritual—but I don’t want to be as vulgar as they were.

I wondered, then, if Black mothers could overturn school buses if the children on the buses, if the children trying to integrate, were openly gay boys and openly trans girls—who are amongst the most despised of all children. My heart instinctively wants to say no. I can’t imagine that anybody wants to think of members of their own tribe as being capable of such a complete moral collapse (which only gets recognized as such in hindsight because in the moments it’s practiced, it’s cherished as righteous). I can feel the knee-jerk denial rising up in my throat like bile. The impulse to grant excuses—to cop pleas, to deflect, to lie, to claim common things are “rare,” to insist that one thing is somehow not like the other—is strong. But my mind recalls the wrath. My soul recognizes the drill. Mine eyes have seen this road before. I know where it leads.

As Morrison, herself, once wrote in her novel, Love:

“Hate does that. Burns off everything but itself, so whatever your grievance is, your face looks just like your enemy's.”

And in this instance, she was correct. Because look:

So maybe I should re-evaluate those old, humiliating poems. Maybe they weren’t terrible at all. Maybe they were just testimony.

I stopped writing poetry over 20 years ago. A fine experiment and zero regrets for the journey since it led me here. I hope I continue to be brave enough to be a witness. And I hope I’m a better novelist/essayist than I was a poet. All of it is important, though. I think I’ve said before that if the effect of reading fiction is the development of critical thinking and empathy, then I think the act of reading poetry heals all sorts of wounds—particularly the ones that lead us to treating other human beings as less than ourselves, that have us poisoning the planet rather than nurturing it, that make us bomb children instead of raise them. Shit, elephants are better at rearing, protecting, and cherishing their kids than we are. When it comes to children, irrespective of the child’s identity, I think the word that best describes our behavior toward them is terrorist. I think that last part is the reason poetry is considered a “dying art form” or is thought of as trivial, inconsequential, invalid, or useless. Anything that exposes how what we claim about our love for children is fully contradicted by our actions, we seek to belittle, discredit, silence, or abolish.

“Dictators and tyrants routinely begin their reigns and sustain their power with the deliberate and calculated destruction of art: the censorship and book-burning of unpoliced prose, the harassment and detention of painters, journalists, poets, playwrights, novelists, essayists. This is the first step of a despot whose instinctive acts of malevolence are not simply mindless or evil; they are also perceptive. Such despots know very well that their strategy of repression will allow the real tools of oppressive power to flourish. Their plan is simple:

1. Select a useful enemy—an ‘Other’—to convert rage into conflict, even war.

2. Limit or erase the imagination that art provides, as well as the critical thinking of scholars and journalists.

3. Distract with toys, dreams of loot, and themes of superior religion or defiant national pride that enshrine past hurts and humiliations.”

—Toni Morrison, “No Place for Self-Pity, No Room for Fear,” The Nation, March 23, 2015

Poems, too, are powerful evidence of humanity. Well, maybe spiders with their webs, birds with their nests, and termites with their hills are creating a kind of poetry, too. But that’s another kind of proof, I think—a declaration of existence, intelligence, and sublime intention, maybe. I’m talking specifically about the Word, though; about the way it’s written and what higher aspirations can be suggested when presented in poetic equation.

If poetry isn’t a mark, possibly the mark, of human confirmation—because what is poetry but song? And song has been the sign of soul since the dawn; and the first people to sing were Black people, because we were the first people—Thomas Jefferson wouldn’t have been so steam-pressed to make other white folks believe that Phillis Wheatley Peters wasn’t a poet. He tried to say that she was a signifying monkey, capable of nothing more than a hollow, thoughtless mimicry of white art and intellect. It’s clear to me that he was deathly afraid (like, perhaps, all white people are deathly afraid, of: the turning of the tables, of what goes around comes around; which might explain their commitment to violence, with their generational curses and sexual attraction to guns) of some unavoidable truths:

Wheatley was, in fact, a human being, which is indisputable; and anyone arguing against that describes not Wheatley’s, but their own exile from the human family;

Wheatley had at her disposal the most beautiful language and wit with which to describe both her condition and Jefferson’s crimes (and his rap sheet is long AF: kidnapping, terroristic threats, forced labor, grand larceny, aiding and abetting, assault, rape, depraved indifference, attempted murder, and if any enslaved people died under his thumb, murder—to say the least).

Affording Black people humanity effectively makes whiteness of no heavenly value or earthly use, since whiteness requires the dehumanization and degradation of Black people in order to not just prosper, but exist.

Trump/Vance/Musk are very much like Jefferson in that respect. They are the direct descendants of his deficiencies if not of his blood. They, too, would rather not think of Black people (or Muslims or Jews or trans people or Brown people or Asian people or queer people, or, or, or fucking or!) as people. They, too, prefer that their crimes be regarded as achievements. The proof is in how they recently decreed that Maya Angelou’s works be removed from the halls of power while making sure to enshrine Adolf Hitler’s in those same halls.

Poetry, it appears, be having despots pet(rified). And whatever scares the autocrats? Yeah, let me go on ahead and carry my ass in that direction because I know it points toward liberation.

“For in a warm climate, no man will labour for himself who can make another labour for him. This is so true, that of the proprietors of slaves a very small proportion indeed are ever seen to labour. And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep for ever: that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation is among possible events: that it may become probable by supernatural interference! The almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest.”

—Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (1781)

Rather than being seen by a poem, I want to be read by one. I mean palm-read and read-for-filth. I would like to divest from the mass narcissism that has grabbed hold of the globe as part of an impenetrable vanity incentivized and glorified by technology. I don’t need another thing lying to me on purpose (if I was religious, that’s what I would consider “the Devil’s work”) so that I wander around, a plumb and dusty fool, actually believing that:

the world is my toilet

purity exists

beauty is more important than mercy

I have no flaws and make no mistakes (I’m god); and any flaws I do have or mistakes I do make are somebody else’s fault and somebody else’s responsibility (everybody else is the devil)

I’m “innocent”

I have no further work to do

I do “everything right” therefore I’m exempt from the laws of reality

I’m above reproach

Only I (or people exactly like me) can be a victim

I can never be a victimizer

the rules apply to everybody except me

embodying the proper arrangement of identities, marginalized or otherwise, excuses me from accountability

it’s okay for me to weaponize my traumas against other people and call it activism

most importantly, I can experience harm, but I cannot commit it.

I want to leave behind, far behind, the places where nothing—not love, not decency, not honor, not pleading, not sense—can come between cults and their gods, especially when the gods the cults are worshiping are really just their own egos magnified. No more dwelling in the land of gimme, where there are hundreds of millions of consumers, but very few people. I don’t need another ounce of the bullshit that would have me out here bringing hella disgrace to myself and my whole line by thinking I’m better than anybody else, thereby placing forgiveness out of my own reach.

Nah.

I want to engage with things that make room for my humanity instead, that afford me grace because I’m alive and, therefore, still have an opportunity: to do better; to make amends; to recognize that when I point a finger at somebody else, three fingers on that same hand are pointing back at me; to be the change I would like to see in the Universe.

I want to be a student of the spirit that challenges me to see myself through something other than rose-colored lenses, to survive that encounter, and to heal—which is, apparently, the most difficult thing for a human being to do, given how much we love to inflict pain; and moreover, how much we love to leverage our own pain: make it commercial, deify it for various purposes, including lording it over others, but none more than to escape rigorous self-inventory.

I want to find the ugly inside of me—and I know it’s there because I’m alive—and root out as much of it as I can until I’m no longer alive. In other words, as James Baldwin once put it (minus the cussing):

I want to grow the fuck up.

“I am not a race and neither are you. I’m not joking when I talk about White History Week. One of the things that most afflicts this country is that white people don’t know who they are or where they come from. That’s why you think I’m a problem. I am not the problem; your history is. And as long as you pretend you don’t know your history, you’re gonna be the prisoner of it. And there’s no question of your liberating me, ‘cause you can’t liberate yourselves. We are in this together. And finally, when white people talk about progress in relation to Black people, all they are saying, and all they can possibly mean by the word ‘progress’, is how quickly and how thoroughly I become white. I don’t want to become white; I want to grow up! And so should you.”

— James Baldwin, addressing the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. (December 10, 1986)

I think art holds the best chance for moving us in this healing direction (though I learned that we must be selective about which art). And it might be the poets who are most prepared to light the course.

Blesséd be the poets. Enjoy the rest of your National Poetry Month.

And Happy Earth Day. Please be kind to the planet and everything on and around it.

xoxo,

Robert

Recommended Reading

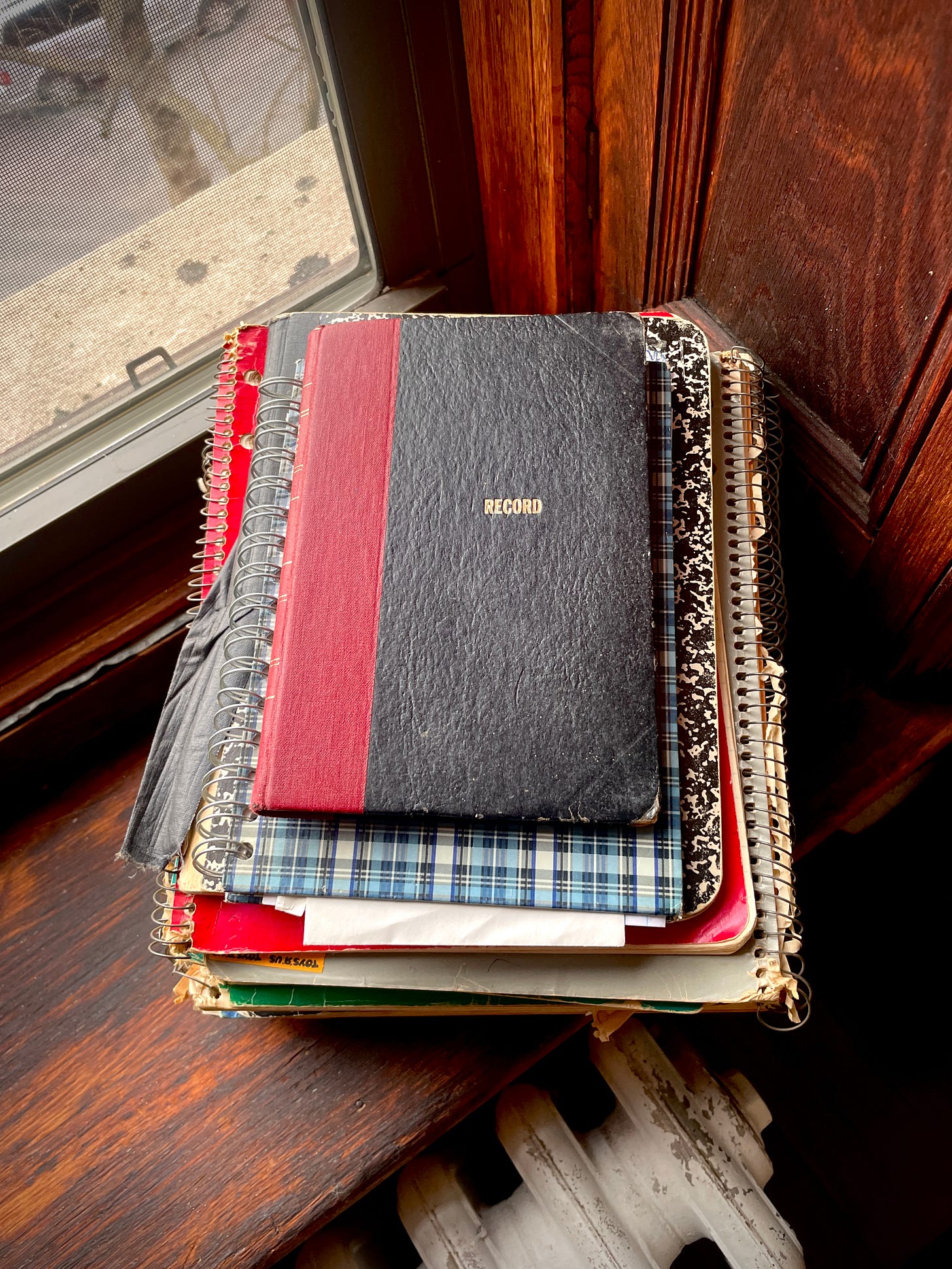

Doggerel: Poems by Reginald Dwayne Betts

Reginald Dwayne Betts is our foremost chronicler of the ways prison shapes and transforms American life. In Doggerel, Betts examines this subject through a more prosaic―but equally rich―lens: dogs. He reminds us that, as our lives are broken and put back together, the only witness often barks instead of talks. In these poems, which touch on companionship in its many forms, Betts seamlessly and skillfully deploys the pantoum, ghazal, and canzone, in conversation with artists such as Freddie Gibbs and Lil Wayne.

Simultaneously philosophical and playful, Doggerel is a meditation on family, falling in love, friendship, and those who accompany us on our walk through life. Balancing political critique with personal experience, Betts once again shows us “how poems can be enlisted to radically disrupt narrative” (Dan Chiasson, The New Yorker)―and, in doing so, reveals the world anew.

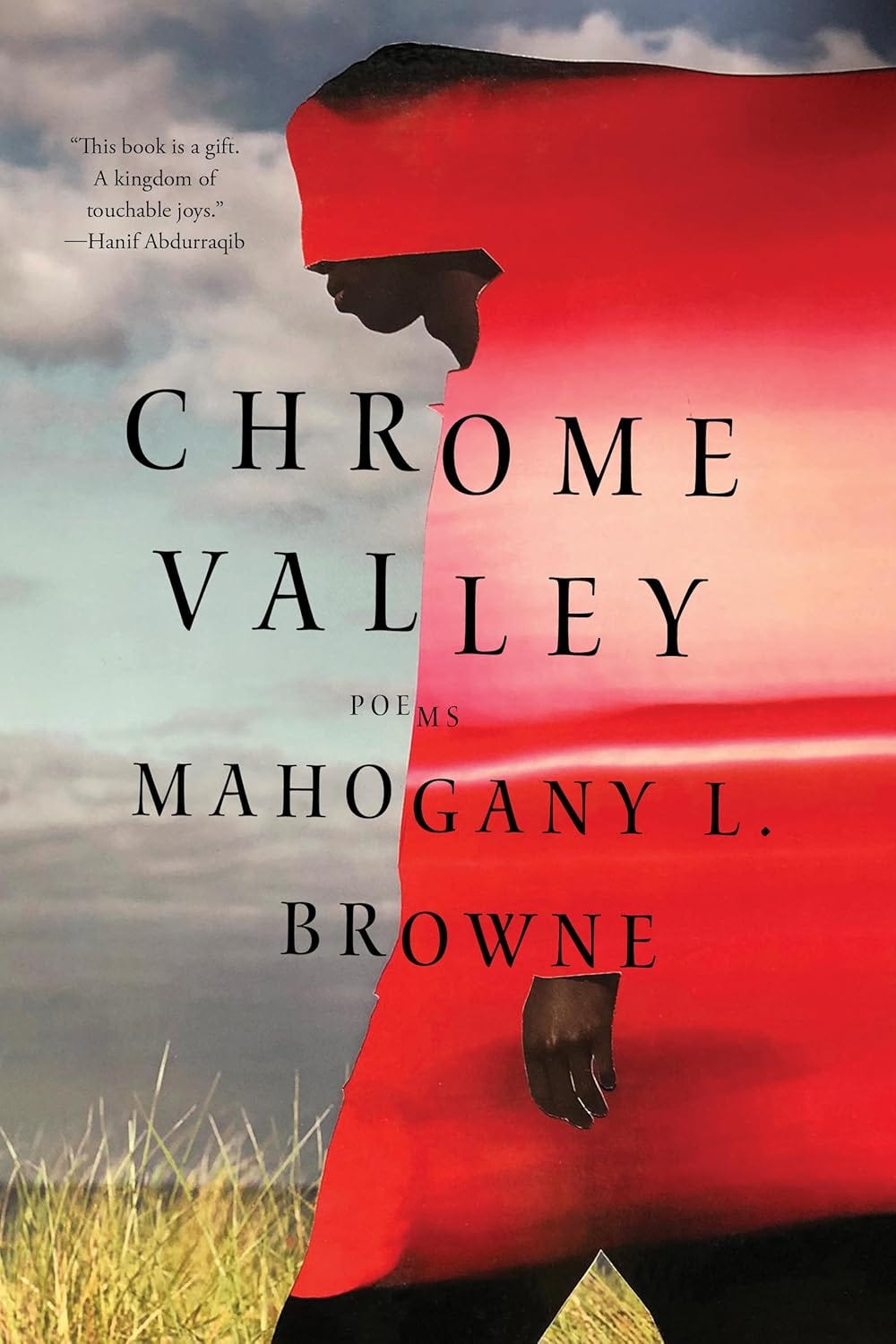

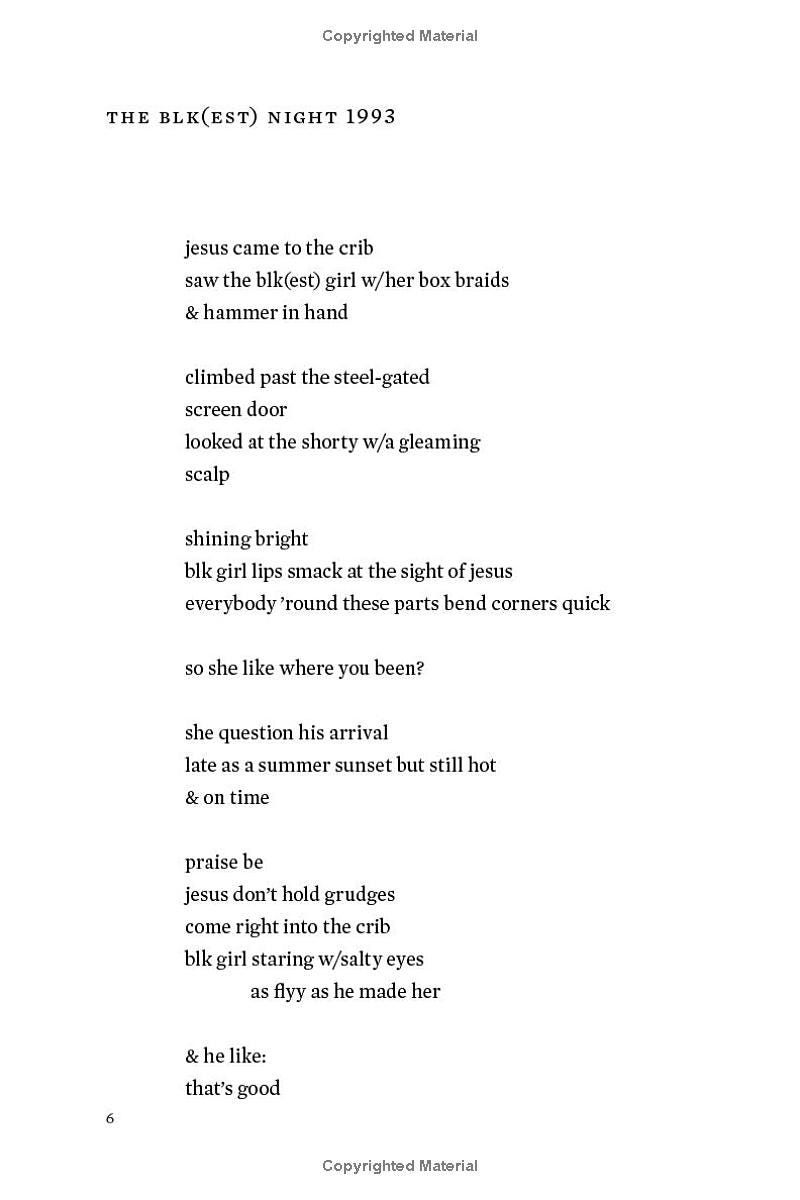

Chrome Valley: Poems by Mahogany L. Browne

Boldly lyrical and fiercely honest, Mahogany L. Browne’s Chrome Valley offers an intricate portrait of Black womanhood in America. Browne captures a quintessential girlhood through the pleasures and pangs of young love: the thrill of skating hip to hip at the roller rink, the heat of holding hands in the dark, and, sometimes, the sting of a palm across the cheek. Friendship, too, comes with its own complex yearnings.

Reflections of Browne’s mother, Redbone, bolster the collection with moments of unwavering strength. Other moments explore the inherent anxieties shared among Black mothers, rhythmically intoning names like the tolling of a church bell.

The characters in Chrome Valley grapple with the legacies of inherited trauma but also revel in the beauty of the undaunted self-determination passed down from Black woman to Black woman. Transcendent and grounded, funny and furious, Chrome Valley brings depth to a movement, solidifying Mahogany L. Browne as one of the most significant poetic voices of our time.

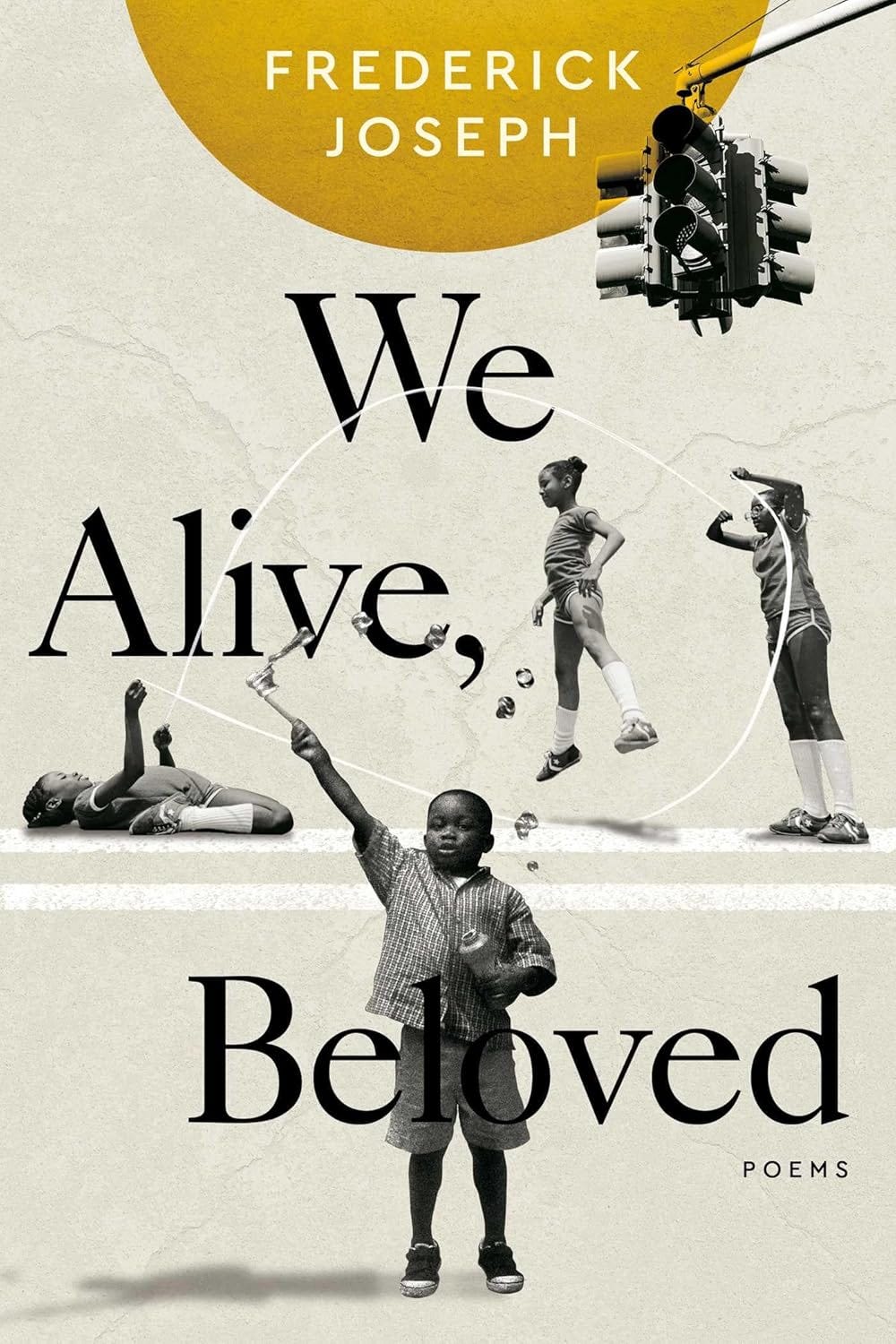

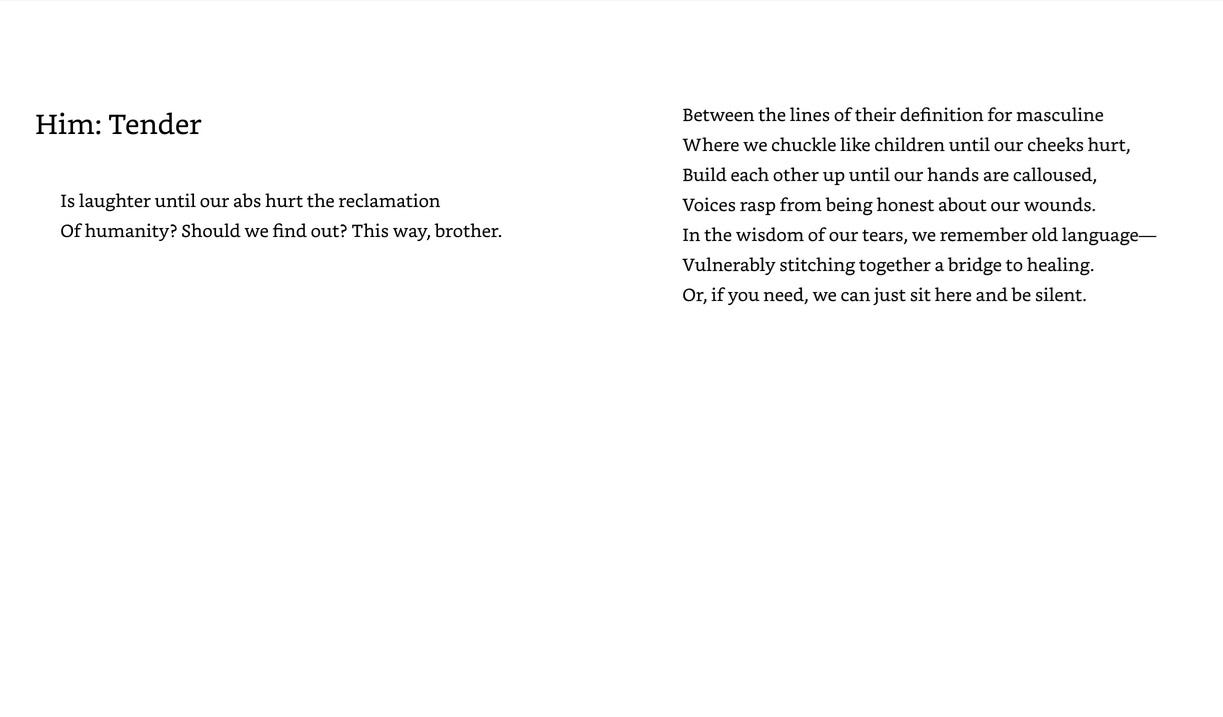

We Alive, Beloved: Poems by Frederick Joseph

NYT Bestselling Author Frederick Joseph explores a new genre in this captivating poetry collection that seeks to find joy in moments of difficulty whether through illuminating the beauty of being Black, highlighting the hope that can be found in childhood, or by sharing intimate truths revealed on a mental health journey. This book will appeal to both new and established readers of poetry.

Step into the world of We Alive, Beloved, where its words will resonate within the deepest corners of your soul, leaving a mark on your heart and a renewed appreciation for the beauty of being alive.

We Alive, Beloved moves beyond being a poetry collection; it's a celebration of the profound aspects of our existence. Each poem seeks to immortalize the fleeting moments of joy, love, resilience, and inspiration that often slip through the grasp of our fast-paced lives.

In this poetic testament, we defy the ephemeral nature of beauty and goodness, daring to clutch onto these facets of life for just a little longer. With words that stand as guardians against the relentless march of time and the ceaseless tides of change, trauma, and grief, this collection becomes a sanctuary of light in a world that sometimes seems dim.

We Alive, Beloved explores a rich tapestry of themes, from the intricacies of relationships and the heartache of loss, to the wide-eyed wonder of existence and the challenges of exploring the possibility of parenthood in our modern age. Each poem reaches out to readers, offering a mirror to their own journeys and emotions, inviting them to be seen and acknowledged in its lyrical embrace.

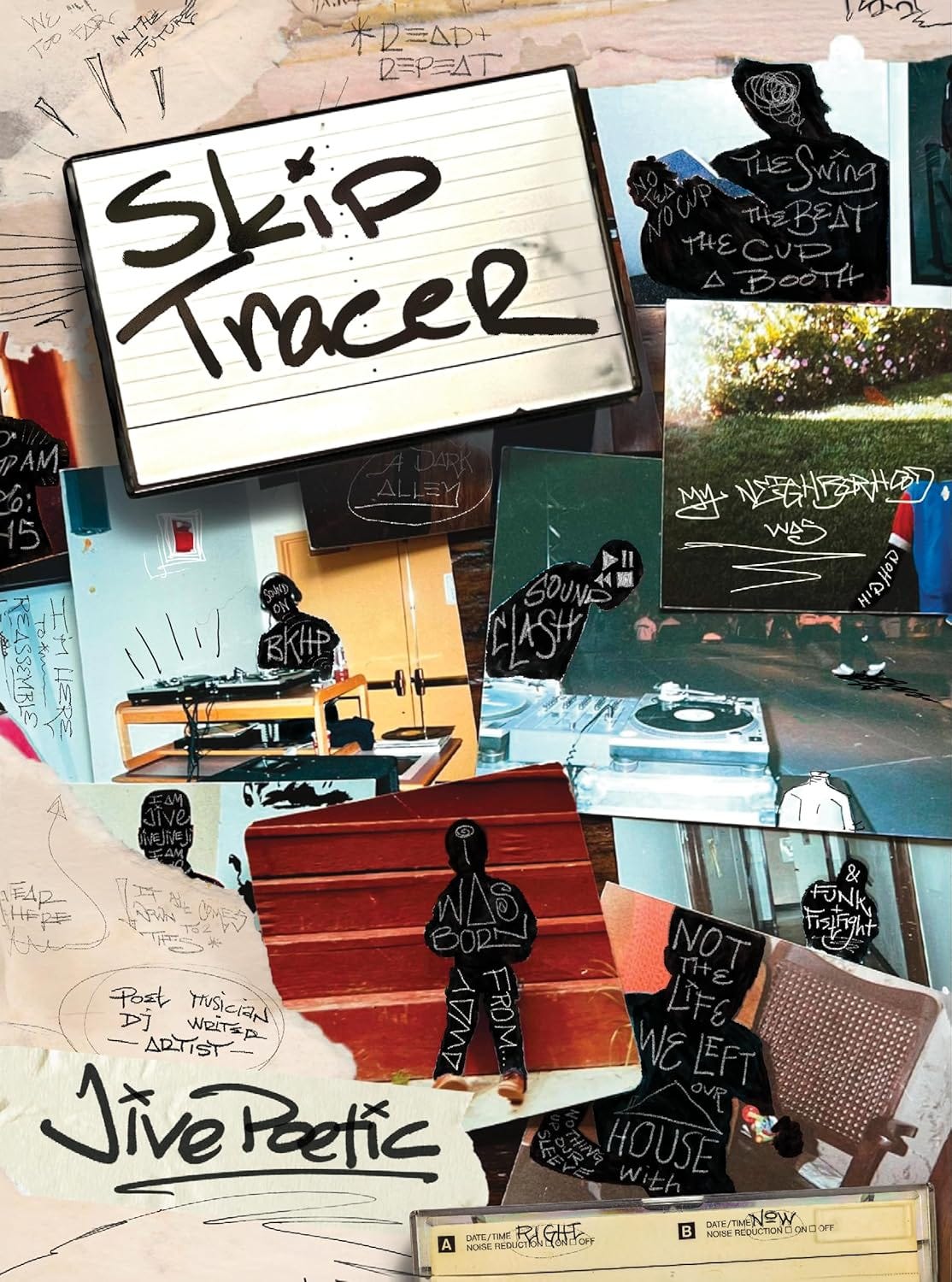

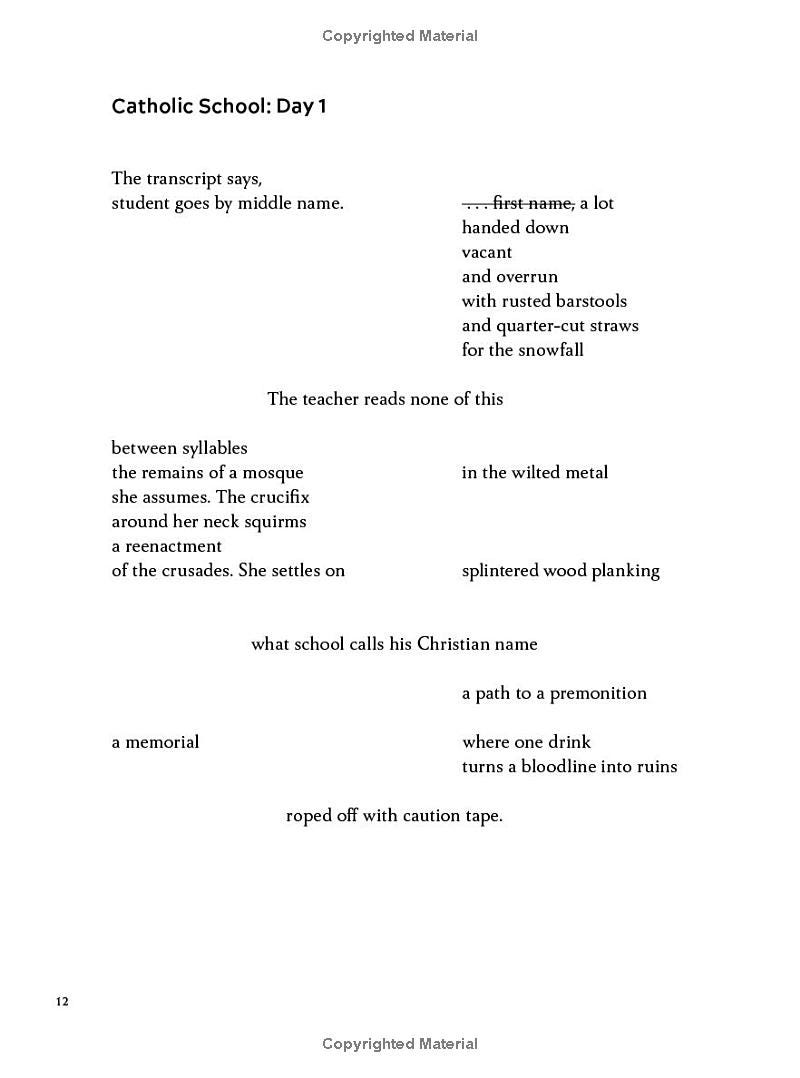

An innovative memoir―composed of poems, prose, and photographs―that engages with the Afro-Caribbean diaspora, cultural identity, music, and masculinity, by a poetry legend.

Blending poetry and prose, music, and genealogy, Jive Poetic’s Skip Tracer is a memoir structured as a “hybrid sound system” (complete with “records,” “tracks,” “decks,” and “channels”), expertly curated to convey the complexity of Blackness in the Americas. In this ancestral and cultural excavation, Jive conducts archival and oral-history research into his family’s connections to Jamaica, Panama, Brazil, and Cuba to explore the impact of culture, environment, and family on first- and second-generation Black Americans in the United States. He also traces the profound influence that hip-hop, soul, R&B, reggae, and other popular musical genres have had on him―all the while performing a dynamic re-creation of his legendary onstage persona on the page. A raw and affecting indictment of police violence and racism in the United States, Skip Tracer is also a searingly honest exploration of personal identity, power, and privilege―all expressed in the unmistakable language, rhythm, and style that characterizes Jive’s live performances.

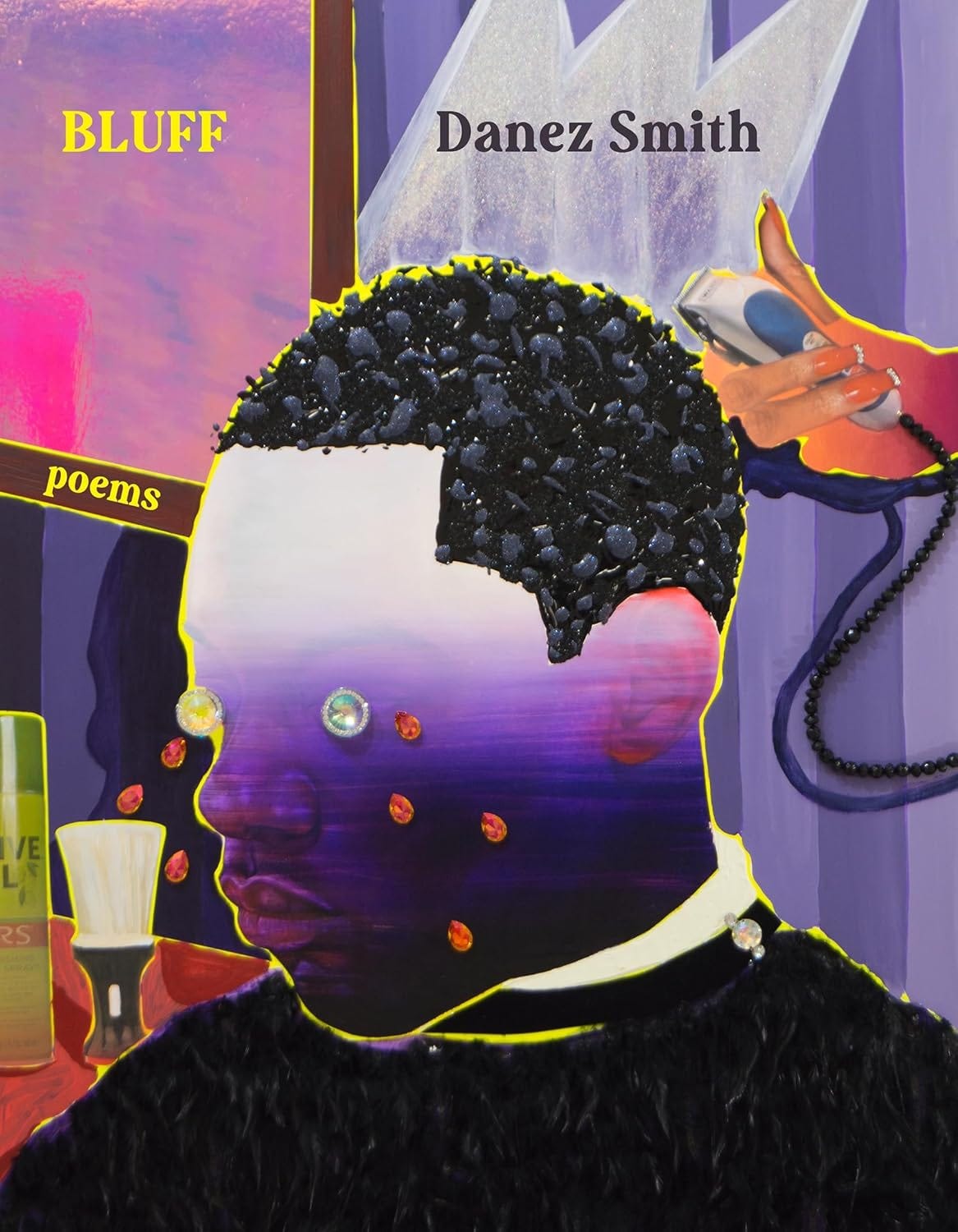

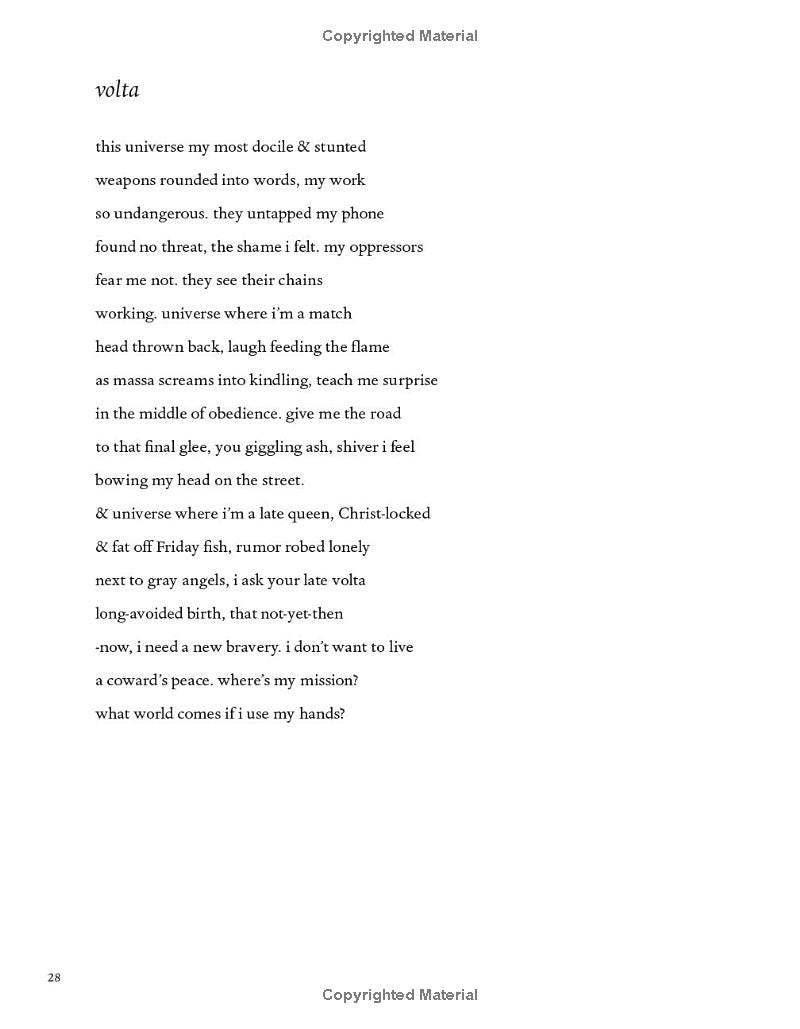

Written after two years of artistic silence, during which the world came to a halt due to the COVID-19 pandemic and Minneapolis became the epicenter of protest following the murder of George Floyd, Bluff is Danez Smith’s powerful reckoning with their role and responsibility as a poet and with their hometown of the Twin Cities. This is a book of awakening out of violence, guilt, shame, and critical pessimism to wonder and imagine how we can strive toward a new existence in a world that seems to be dissolving into desolate futures.

Smith brings a startling urgency to these poems, their questions demanding a new language, a deep self-scrutiny, and virtuosic textual shapes. A series of ars poetica gives way to “anti poetica” and “ars america” to implicate poetry’s collusions with unchecked capitalism. A photographic collage accrues across a sequence to make clear the consequences of America's acceptance of mass shootings. A brilliant long poem―part map, part annotation, part visual argument―offers the history of Saint Paul’s vibrant Rondo neighborhood before and after officials decided to run an interstate directly through it.

Recommended Listening

Recommended Viewing

If you are so inclined, please think about donating to your favorite children’s charity. Among those I recommend are the Center for Black Equity, the National Black Child Development Institute, the Palestinian Children’s Relief Fund, the Trans Youth Equality Foundation, and the Trevor Project. Thank you.