The Politics of Wondering: Gender, Nationality, Race, Sexuality, and War Vis-à-Vis Tom King's WONDER WOMAN #1

“America versus Wonder Woman.”

Please note: This review will contain spoilers. Thank you.

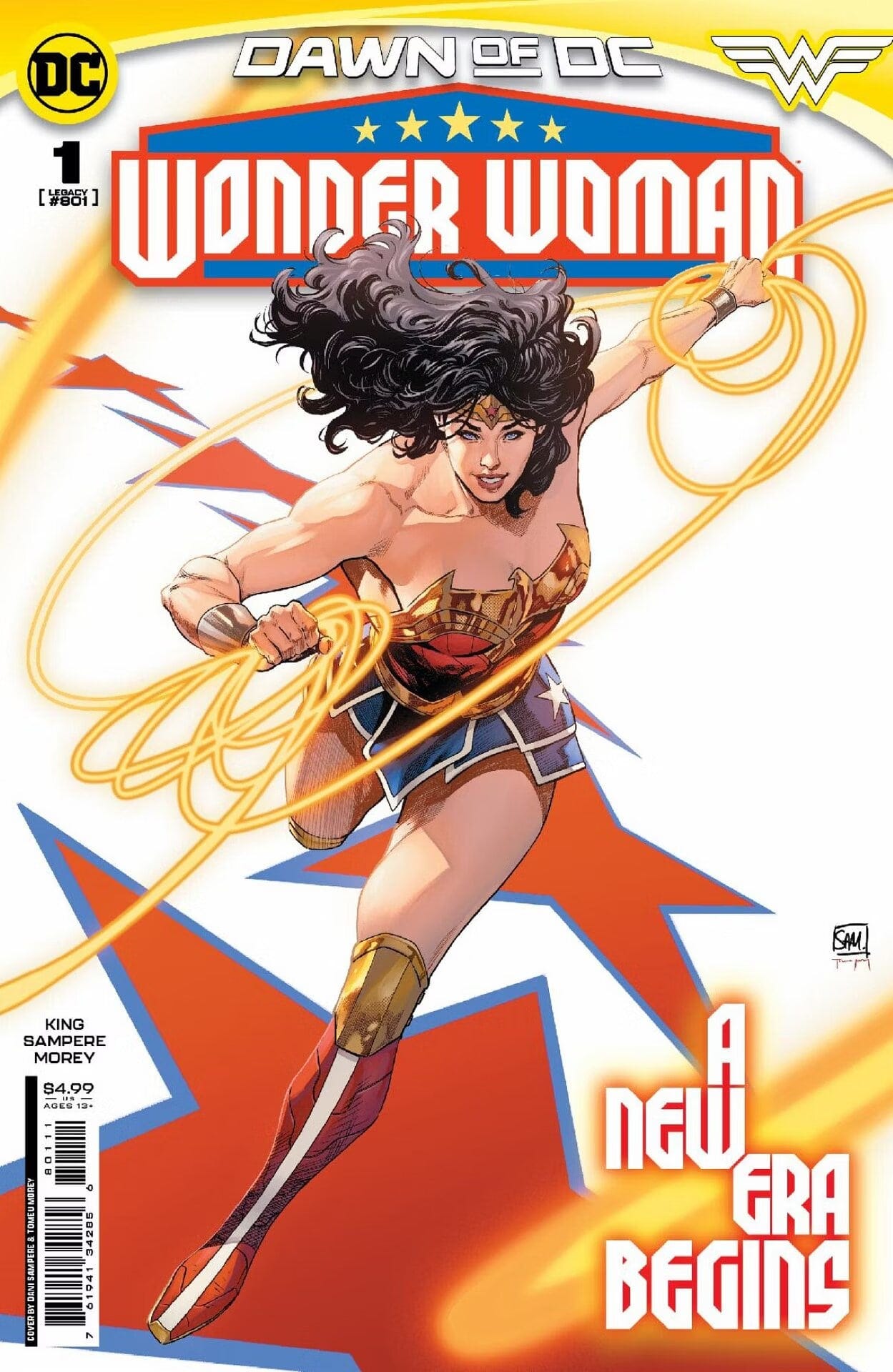

Wonder Woman #1

“Wonder Woman: Outlaw, Part 1”

Writer: Tom King

Artist: Daniel Sampere

Colorist: Tomeu Morey

Letterer: Clayton Cowles

Editor: Brittany Holzherr

Associate Editor: Chris Rosa

Group Editor: Paul Kiminski

Publis…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Witness to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.