Message to Michael

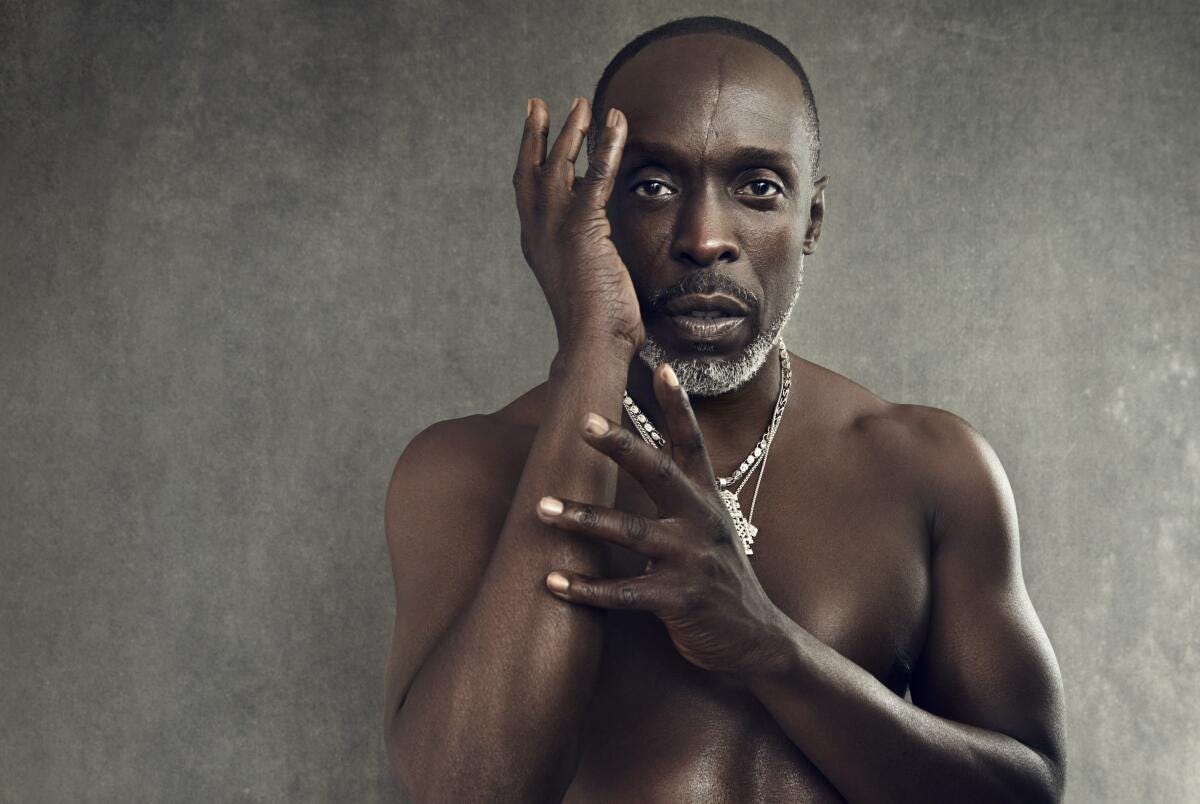

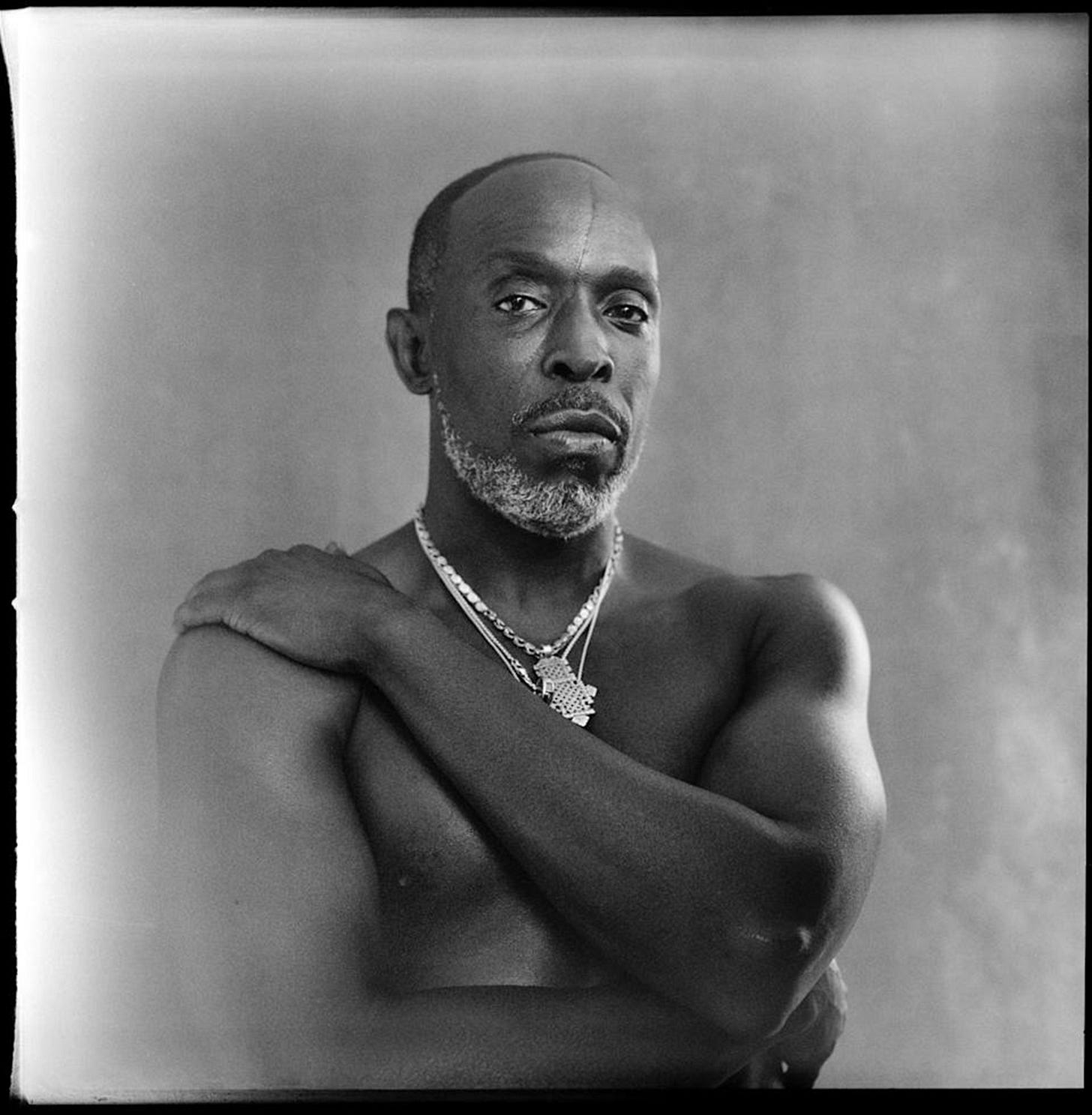

Michael Kenneth Williams (November 22, 1966 - September 6, 2021)

The artist Michael Kenneth Williams would have been 59 years old today.

Instead, he died, under deeply sorrowful circumstances, here, in Brooklyn, New York, on September 6, 2021, at the age of 54, the age I am now. I never met Mr. Williams, but his death impacted me greatly. I think that is because I felt a fictive kinship with him, mentally adopting him as the older brother I never had. I imagined him to be the kind that would teach me things, like how to fight, how to laugh, how to be brave, how to dress, how to dance, how to love, how to make a dollar out of fifteen cents, and how to survive a world determined to kill me.

Part of the grief that visits me each time I come across a film, a television show, or a photograph of him is knowing that he is part of a concerning epidemic among Black men in America, one in which communities, customs, and institutions conspire to ensure that many of us do not reach the age of 60. I am not a social scientist, but I am a Black man. So, I often wonder how the pressure for Black men to be the protectors, the providers, the performers; to be the monsters and the scapegoats for everything wrong in society; to be everything except human beings, factors into things like the explosive tendency toward self-harm.

Because I do not have the answers on how to solve major social ills like that one—or, at least, no answers that anyone is willing to listen to, much less enact—I have to write through my grieving. Back in 2021, shortly after Brother Michael’s death, I wrote “Message to Michael” on the Son of Baldwin social media platform:

Message to Michael

Kentucky bluebird, fly away/And take a message to Michael/Message to Michael/Tell him I miss him more each day.

– Dionne Warwick, “Message to Michael”

I’ll be honest: I was unprepared for your departure, Michael.

I’m mad that you’re gone, at how you’re gone.

To anesthetize oneself in a world like this, though? It makes sense. To take the risk. To choose possible oblivion over this. As a Black man in a world where both Black and man are rendered dangerous, why not do relatively quickly what the world, in its sadism, can sometimes take too long to do? Why not feel a measure of peace, of ecstasy, before the harm placed inside by foolish minds claims the outside, too?

I get it, Brother. I do. How all of us aren’t using what you used, plotting our own demises, is nothing short of a miracle.

But what cuts me to the quick is that I know not even love could have saved you. There isn’t enough love in the multiverse to counter the way the world uses you up. They are greedy for your guts while simultaneously claiming you don’t have any. But here we are, moving about in a world so thoroughly cruel that it can’t even admit to it because that would be too much like truth. And truth, quiet as it’s kept, is merely another word for love.

Many of our elders, the ones we especially ignore, have already told us that love cannot dwell anyplace where lies reign and vice versa. But I’ll be damned if we don’t still perform anyway, using pleasure as an unsuitable substitute for the real thing. Something is better than nothing, I suppose.

It turns out, then, that we were helpless this whole time. Because, you see Michael, I’m going to be honest for all of us: This pleasure thing that we think is love? It, too, is conditional. We “loved” you if. If you entertained us. If you terrified us. If you made us laugh. If you made us cheer. If you titillated us (which, unsurprisingly, doesn’t take much: your Black-Black skin ignites our imaginations). If you embodied our dreams, our fantasies—the valid ones and the untoward ones alike. We’re not worthy of you, Michael. And we never were. How your nephew found you is an indication to me that you might have known that. People who suffer no delusions about what life actually is often prefer the company of the dead. No one can blame you there.

What choice is left for a man, especially a Black man, in a world that has no room for his softness, his femininity, his frailties, his elegance, or his grace; for the myriad of ways in which he might show up in the world that fits inside no one’s boxes, nor the contours of anyone else’s expectations except his own? His own—which are required to remain eternally concealed because who could live life as the recipient of incessant booing?

Yet and still, you were dancing to Janet Jackson. You kissed niggas on camera when everyone looked at you and expected, no, demanded from you a living malice at the very notion. You were trying to imagine your way out of the coffin they designed specifically for you from the moment of your conception and before.

“A man ain’t a goddamn axe…” Toni Morrison once wrote, but that doesn’t alter the world’s view. You probably knew that too, which is maybe why you decided to leave on Labor Day? A most bitter irony that perhaps gave you the laughter you were never permitted to fully embrace because “real men” can’t laugh out loud; not recklessly or in glorious abandon, lest the whole world question his value. Just work, darky! Produce! Protect! Provide! Let’s see if you can drive that steel quicker than a drilling machine, you John-Henry-ass nigger! Soldier on! March until the end!

Everybody hates patriarchy and everybody loves patriarchy. That might be the first double-edged sword ever forged by human hands. Or human minds.

I hope that in your transition, your example, as tragic as it might feel, inspires or frightens someone who recognizes themselves in you enough for them to choose a different kind of freedom, one that heals as it moves, laughs as it spreads, caresses as it points to the North Star, which is possibly the direction of home in a world of no shelter.

At least it was on your own terms, Michael. At least it wasn’t because some cop said you “fit the description” and shot you in the back because they claimed your can of Arizona iced tea looked like a TEC-9. At least it wasn’t some other person who was raised in circumstances similar to your own, who craved shooting you in the face because they didn’t yet have the knowledge—or the courage—to point the gun in the proper direction. But still, it was the master’s tools. Ask Reagan when you pass him if he now thinks it was all worth it. Do you wonder what his answer will be? Do you think he will express regret or if even in whatever realm is next, if there is a next, he’s resolute in his hatred, and that hatred is what they really mean when they say “the eternal lake of fire”?

Maybe I shouldn’t be writing this while I’m angry, Michael. Because when I’m angry, I’m liable to be profane. Direct, but profane. And why should you ask Reagan anything when the Ancestors are waiting on you, preparing a feast fit not for a king (because kings deserve scorn not feasts), but for an artist who was a witness, and tried to leave the world in better condition than he found it. There’s Grandma’s sweet tea and Grandpa’s barbecue. There’s Auntie’s potato salad and Unc’s sock-it-to-me cake for all the witnesses to honest testimony.

Listen at me. Talking about you as if I knew you personally when I didn’t. But that’s the effect you had on so many of us, Michael. You made the unfamiliar familiar and the familiar sparkle such that we can’t help but to think we knew your insides as well as we know our own. But the simple fact is that we did not know your insides. And, as it turns out, we don’t know our own, either. We, like you, use all manner of things to soften the blow of self-inventory and deny whatever accountabilities that would force us to confront. So you see, Michael: We were more alike than not; our familiarity not so outrageous after all.

I loved you, Michael. I loved you as much as Black men are allowed to love in a loveless place. I’m trying to determine if that means I didn’t love you at all. And if I didn’t, will the rest of my life be spent in search of your forgiveness?

Honestly? I can think of no better use of the remainder of my time here, considering how little of it any of us have left.

Rest now, Brother. Though your life was also ephemeral, your impact is infinite. And if there is any justice in the cosmos, so is your spirit.

Damn! Dear Michael!

How I weep for you.

Recent Notes

Recommending Listening

“Message to Michael” by Dionne Warwick (1966)

Recommending Reading

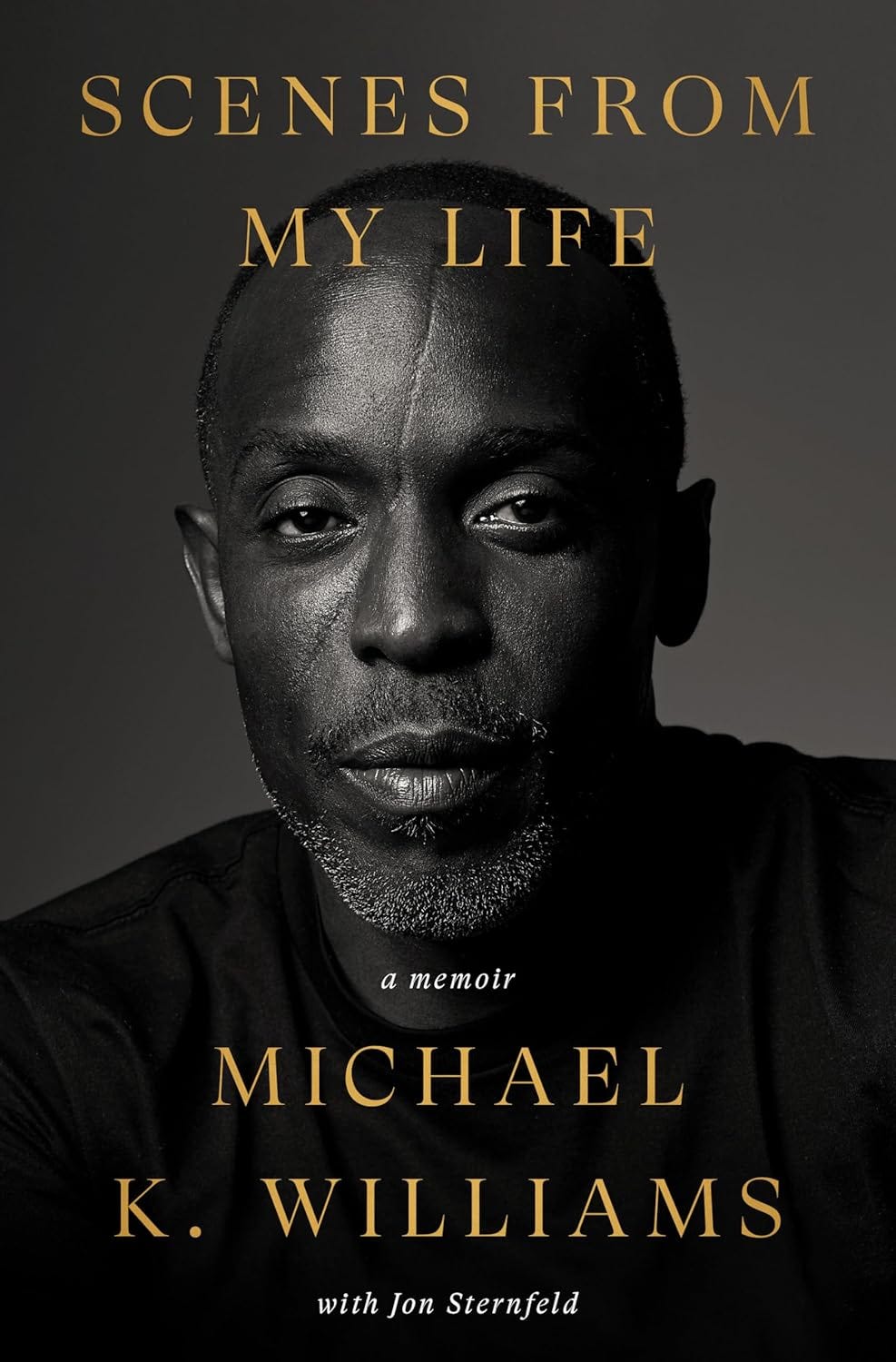

Scenes from My Life: A Memoir by Michael K. Williams (Crown, 2022)

Recommended Viewing

Michael K. Williams Dancing with an Unnamed Partner to “Celebration (Manoo’s Aitf Remix)” by Djeff Afrozila (featuring Ade Alafia) in a Brooklyn Park (2020)