Fine & Dandy

Black men dress for the gawds.

Welcome to Witness, a reader-supported publication writing in the traditions of Black resistance and survival in the age of political suppression. If you find something of value here, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Thank you.

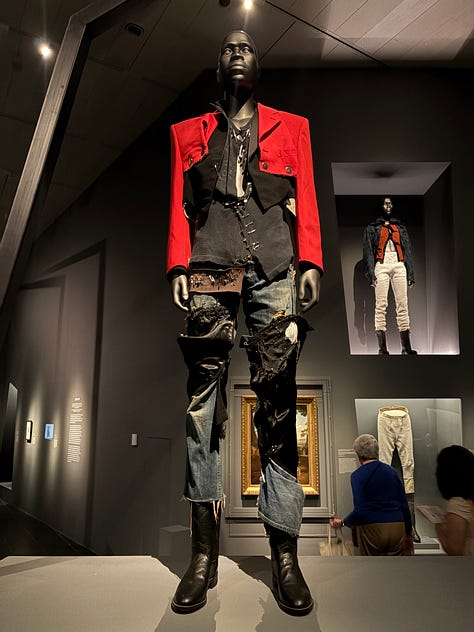

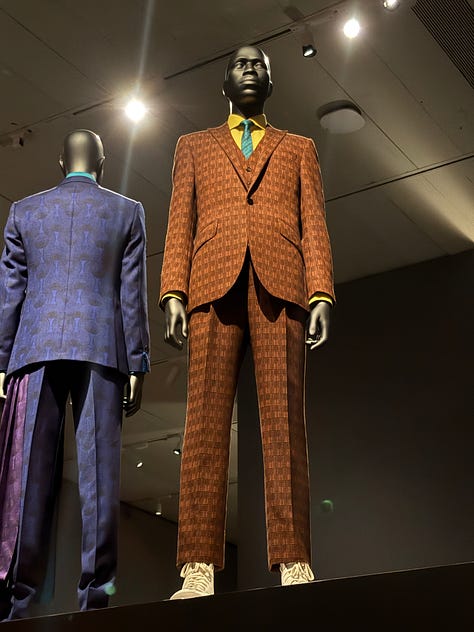

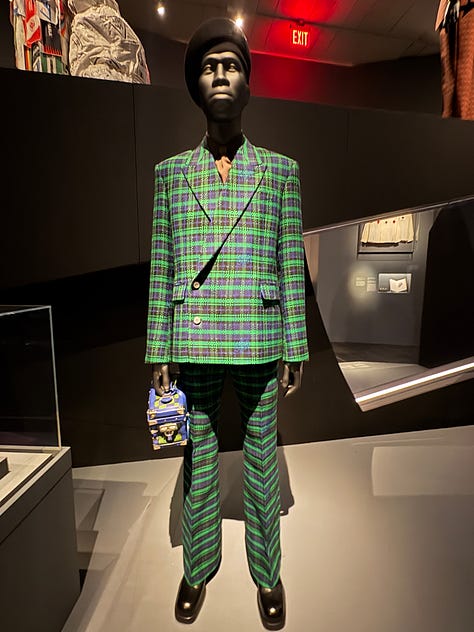

Yesterday, I had the pleasure of visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) in New York, New York, to see the Superfine: Tailoring Black Style exhibit.

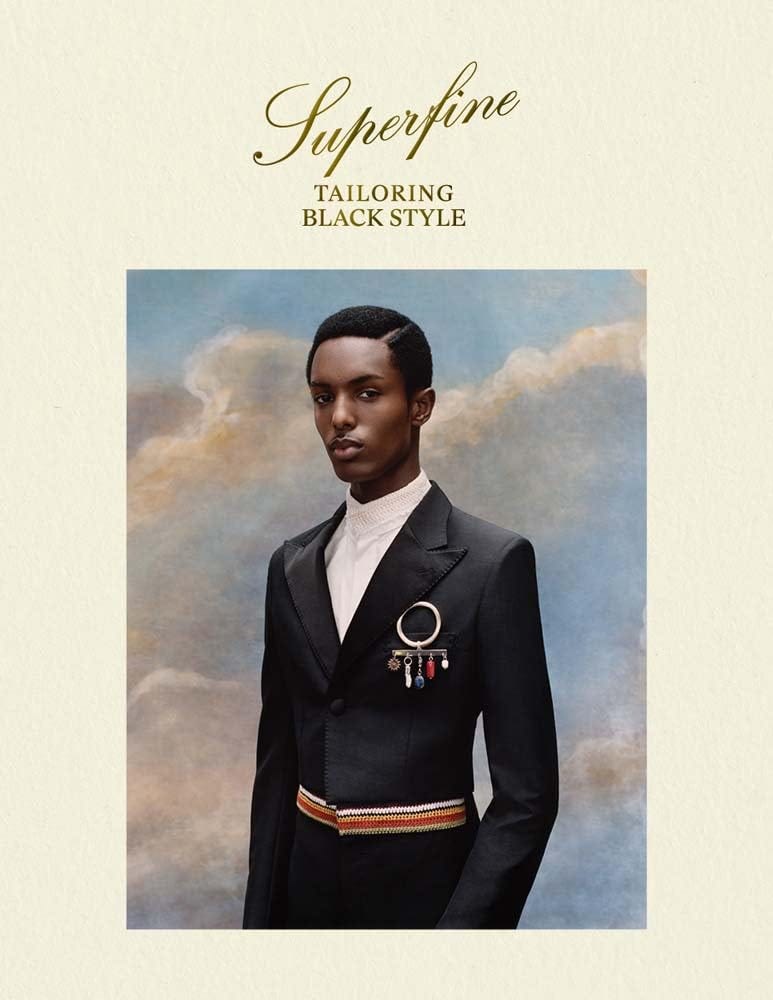

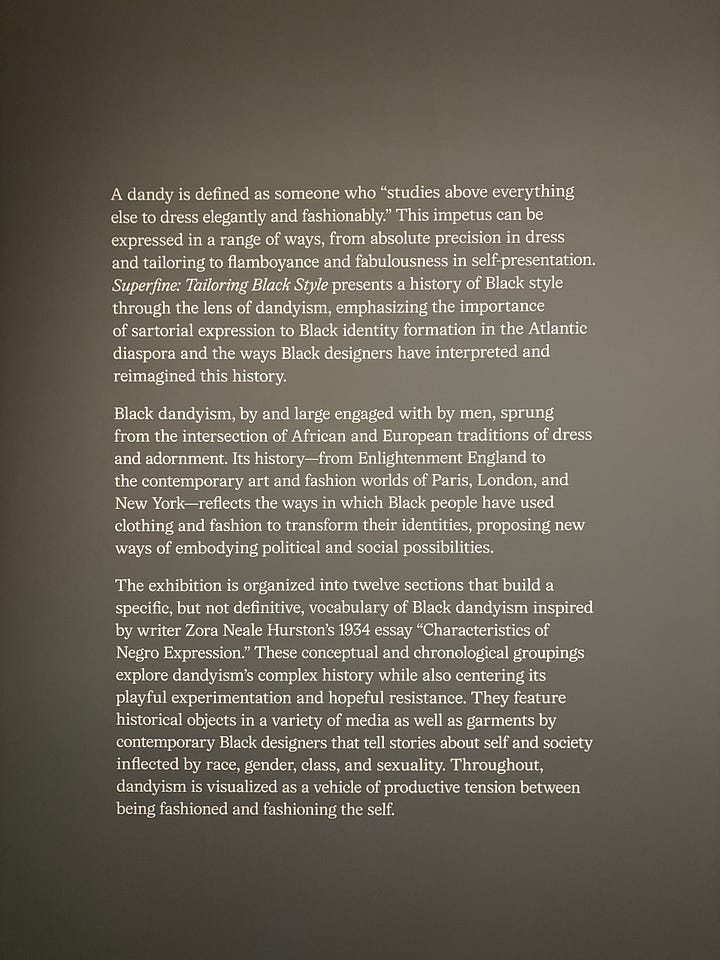

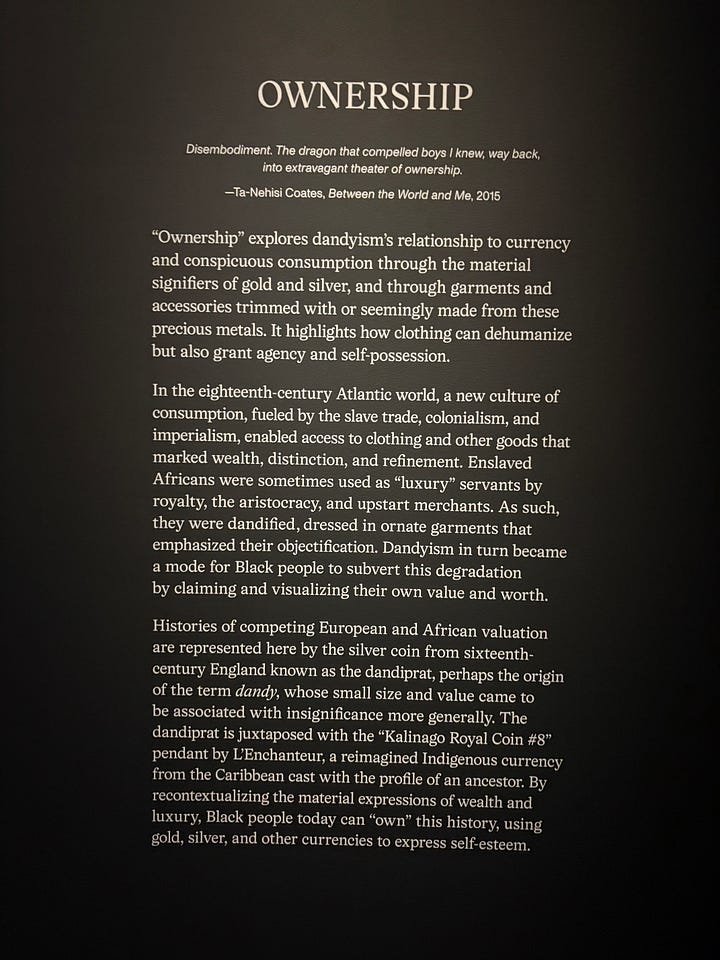

The exhibit is described as “a cultural and historical examination of Black style over three hundred years through the concept of dandyism. In the 18th-century Atlantic world, a new culture of consumption, fueled by the slave trade, colonialism, and imperialism, enabled access to clothing and goods that indicated wealth, distinction, and taste. Black dandyism sprung from the intersection of African and European style traditions.”

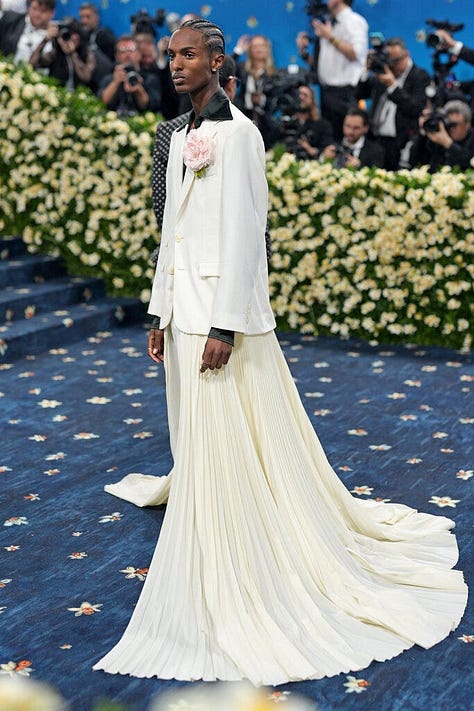

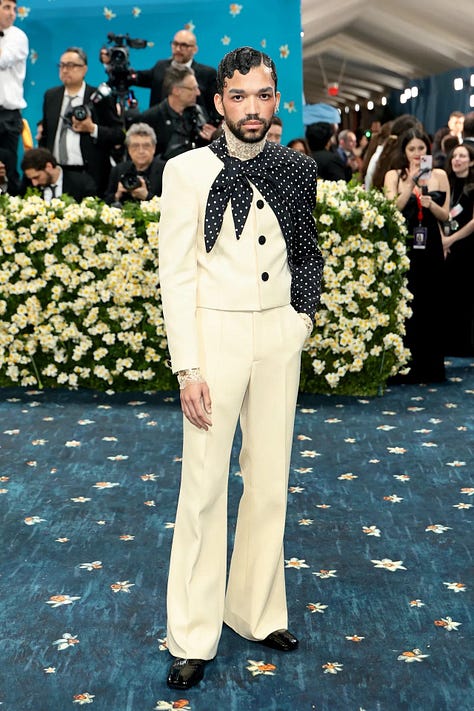

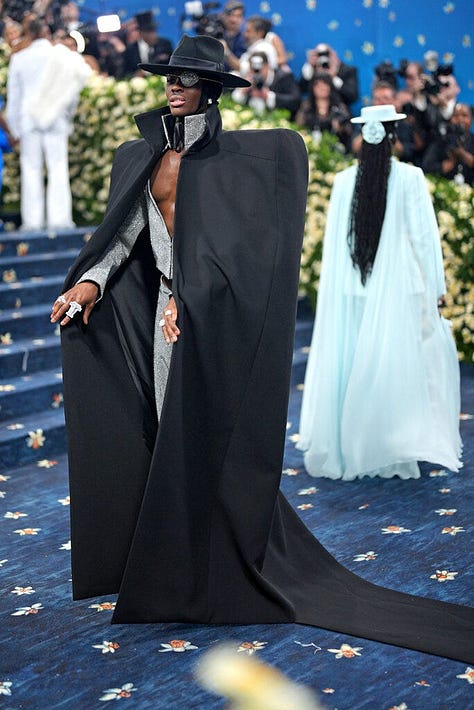

This exhibit was kicked off by this year’s Met Gala, which was organized by Colman Domingo, Lewis Hamilton, A$AP Rocky, and Pharrell Williams, along with honorary co-chair LeBron James. I’m sure you saw the fashions. Here are some of my favorite looks of the evening:

The organizers of Superfine say that “the exhibition interprets the concept of dandyism as both an aesthetic and a strategy that allowed for new social and political possibilities. Superfine is organized into 12 sections, each representing a characteristic that defines the style, such as Champion, Respectability, Heritage, Beauty, and Cosmopolitanism. Together, these characteristics demonstrate how one’s self-presentation is a mode of distinction and resistance—within a society impacted by race, gender, class, and sexuality.”

That last part is crucial. In some places, the word dandy was used as a pejorative to describe men who were overly concerned with their appearance. Beyond merely vain, the suggestion is that it is “effeminate” or “gay” (or, in today’s parlance, “sassy”/”zesty”) to have such a characteristic. While it’s not often the focus of mainstream conversations, dandyism, as an identity, is a precursor to queerness; and many of the Black men (and others) who embraced the style were not just making fashion statements, but sociopolitical ones as well. They were attempting to break free of the patriarchal expectations regarding gender, gender expression, race, and sexuality that were (and are) forced upon Black men.

And they did so with enormous sartorial flair! Oh the drama, honey! The draaamaaa!

There is a tendency to belittle fashion, to think of it as a frivolous and bourgeois endeavor that takes up the valuable space that we think would be better used to fight injustice. I get that perspective. But I also agree with Toni Morrison in that:

I also see fashion as a deeply rebellious art form that should not be hastily dismissed. Think about it: Nothing causes more of a commotion than a man deciding to wear a dress or a woman deciding to wear—or not wear—a hijab. Furthermore, nobody is more creative and fashion forward than my people, by which I mean the people of the hood. Whether the homeboys, the homegirls, the drag queens, or the sex workers, my folk remix clothing to make it feel fresh and new—that is, when they’re not innovating and setting the very trends that they get neither the credit nor the money for.

As I was walking through the museum, I wondered:

How an exhibit like this might survive the Trump/Vance/Musk regime’s determination to destroy all things Black.

Why the world loves what Black people create, but hates Black people.

If Black people might somehow build our own institutions such that it is Black people who benefit—financially, historically, politically, or otherwise—from such displays of our genius and labor.

Because those are the kinds of questions on my mind as I wander around spaces like this, I usually experience a bit of melancholy alongside the joy; mainly because I don’t know the answers to those questions.

Or maybe it’s because I do.

The Superfine: Tailoring Black Style exhibit will be at the Met through October 26, 2025. Tickets are available on a pay-what-you-can scale.

Recommeded Listening

“Black Dandyism: A Cultural History, an Interview with Monica L. Miller (Part I),” Dressed: The History of Fashion

Recommended Reading

Superfine: Tailoring Black Style by By Monica L. Miller with Andrew Bolton, William DeGregorio, and Amanda Garfinkel; Photographs by Tyler Mitchell

Recommended Viewing

The Gospel According to Andre (2018)

To access the additional commentary, photos, videos, and behind-the-scenes looks below, become a paid subscriber.